History of Shelburne Bay:

Sought after by the mining companies, National Parks, and conservationists; fought for by the pastoral lease holder; under Native Title land claim by the traditional owners, and locked away from the passing traveller are the most spectacular pure white silica sand dunes in the world. Sand so pure, so vast and so white that the dunes appear like rolling snowfields.

Situated between Shelburne Bay and Temple Bay on the eastern side of Cape York is one of the least disturbed areas of active parabolic silica sand dune systems in the world. This area is the traditional home of the Wuthathi people. Here the warm coastal waters and fringing coral reefs abound with dugong and green turtles. The Wuthathi were seafarers and they spent their lives in and out of outrigger canoes gathering food and other resources from the seas and the sand beach country.

In 1959 Dal Nixon was, and I quote from his son Johnny “was offered the first block No ol73. We walked and rode horses to get there and the first road’s were cleared with axes, and the creek crossings dug with pick and shovel”. Dal drove his bulldozer from Weipa to the site on the Harmer River and took up the pastoral lease granted to him and his wife Eileen.

Later in the 1960’s he used that same dozer to push a track out to the Shelburne Beach, and to the silica dunes at White Point, then an access track down to the Olive River.

In the following years prospectors, and naturalists arrived in isolated Shelburne Bay and they were all seeing quite different things in the dunes. The naturalists and ecologists drew up a complex plan for a National Park. Conservation groups made a proposal too compelling for the government to bury and economic interests of the miners made it too inconvenient for them to seriously contemplate. This National Park application went on to set a record for being the longest such un-enacted proposal of its kind.

In 1980 the Bjelke Petersen government had a very active agenda of northern development that favoured the prospectors and the pastoralists and at one stage even a plan for a space station at nearby Temple Bay. The Queensland government issued numerous mining leases for the silica sand and in 1985 a Japanese conglomerate sort approval for a large scale mine, town, processing plant, and port complete with shipping channel blasted through the most pristine areas of the Great Barrier Reef. On the other side the conservationists were still insisting the area should be a National Park; however nobody ever thought to involve the local indigenous peoples.

At the Mining Warden’s Court on Thursday Island, the Japanese consortium through their powerful legal team stated in court that there were no indigenous people from the Shelburne Bay area as they were all dead. This turned into one of those great moments of Australian courtroom drama. Don Henry, the then co-ordinator of the Wildlife Protection Society, located 70 year old Alick Pablo who was born at Shelbourne and was enslaved on the Japanese pearling luggers. He and other ‘white sands people’ were living at nearby Lockhart River. A couple of days later the doors of the court room swung open and old Pablo walked into the packed room where Henry presented “a live, ticking elder of the Wuthathi people”

“The other side looked as though they had seen a ghost,” said Henry. The QC handed Pablo a map and challenging him to “show us where you are from”. Henry recalls that Pablo “looked down at the map, and up at the QC, and then down at the map and then up again and said “You are a funny fellow. You got the map upside down” before turning it around and putting his finger square on Shelburne Bay.

The Mining Warden took the unprecedented step of recommended strongly against the proposal but a furious Bjelke Petersen said it would be going ahead anyway. The Wuthathi and conservationists gave up on the state and jointly approached the Hawke government who said the proposal would not have the go-ahead without a Federal export licence or foreign investment approval. So with that the consortium dropped the proposal.

This fight galvanised the resilience of the Wuthathi people and the Wilderness Society into the ‘Save Shelburne’ coalition for further court room battles, because despite the success, the mining leases remained up for renewal until February 2003.

On a personal side the Nixon’s had suffered. We have been regular visitors to the Shelbourne property since 1991 . Most visitors to the spartan homestead thought of Dal as a cantankerous old fellow, to the extent that for many years, written across the Shelburne Homestead roadside sign was “Cranky old bastard lives here”.

However we were always greeted with a smile, a handshake and a long yarn about everything including the “bloody no-hopers”.

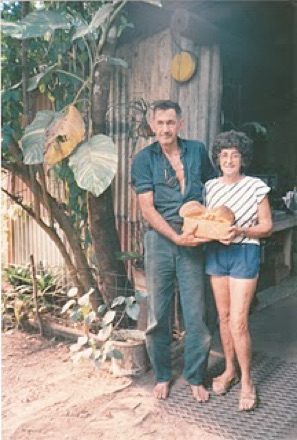

Eileen’s bread was something to enjoy over a cuppa or two in the very basic but clean accommodation.

As the fight progressed Dal became a little thinner and a little crankier. Eileen moved out of the homestead around 1994 and according to Dal “was very busy mixed up fighting those buggers saving the Cape”.

By 2005 he had suffered a stroke and was taken from the property and is currently residing in a nursing home in Mareeba.

Time was on the side of the opposition and the homestead was just left in the moment. The sink was left stacked with pots and pans, old papers and bottles covered the floor. In his final days at the ‘house’ he was living on a diet of tined camp pie and pears and there were lots of both on the shelves with rust starting to take hold. The outside was a junk yard full of broken stuff. The old lawn mower, well past its used by date in the middle of the chook yard, his Landcruiser ute, the Blitz truck and that dozer was slowly been taken over by the environment.

Back in Brisbane, with the mining leases still open the Wilderness Society and a number of eminent members of the scientific and political community lobbied the government. Finally on the on 24 March 2003, Premier Peter Beattie convened a press conference and announced that the State Government would legislate to protect ‘the pristine sand dunes of Shelburne Bay from mining’.

The twenty year fight was not over for the Wuthathi Tribal Council because they still had to contend with that National Parks application. They and the conservationists were both concerned how the “under-funded” National Parks would protect the area and recognise its cultural significance. Lyndon Schneiders, spokesperson for the Wilderness Society said “We can understand the Wuthathi people looking at other poorly funded parks on the Cape and not being impressed” he continued “We think there is a place for a properly funded, Indigenous managed park and here is a great opportunity for the government to get it right. But the bottom line is if the Wuthathi don't want a National Park, we won't support it.”

In future, whoever manages this area I do hope we can all enjoy this special place.

Post Note

Dal passed away in 2013.

Quote from Johnny Nixon

“Dal snapped his hobbles and his ashes were scattered in the original horse paddock and a headstone erected at the loading ramp of the cattle yards.”

Our re-exploration October 2009:

Shelburne Bay is a diverse, complex and unusual landscape that changes as one leaves the Nixon homestead and follows the 80 kilometres of track out to the coast at White point. We had travelled this track many times since 91’, and often we were the only vehicle to have been out there since our previous bi-yearly visit.

Four bikes, eight people, fuel, water and with gear for a 4 day expedition makes them overloaded. From Bramwell station we followed station tracks for the first 19Km before turning left onto an old shot line that I had GPS marked from maps more than 40 years old. This seismic line connects with Dal’s original bulldozed trail about 6kms south east of the old Nixon residence. More than once we were scouting on foot, retracing our steps, or standing on the quad seat looking for the ‘line’ through the trees.

At 73 kilometres and a day and a half of travelling we reach a small dry platform at the base of a spectacular 100-metre high white dune.

These dunes are active and as such the 45 degree slope is loose sand that is slowly encapsulating the undergrowth.

On the maps this is marked as White Point.(*)

Looking back to the west from the top of the dune we see there are repeated low v-shaped dunes called Gegenwalle ground patterns and are recognised as the best developed and largest in the world. This entire area is unique and one of the few places in coastal tropics where such elongated parabolic dunes are still active.

On a global stage this area is spectacularly beautiful and outstanding in its landform and vegetation diversity yet has remained hidden from the countless Cape York travellers. (*

The Bramwell outstation/fuel stop does take charter flights over the area however, although impressive does not give one the 360 degree wow factor one gets from the top of these white monoliths.

It will be interesting to see if the Wuthathi governance will allow others access to see and appreciate why they fought so hard and long for the protection of this special place.

Our return trip is just as interesting, all those blackened dead fire burnt sticks are now pointing directly at the oncoming quad radiator. We manage to avoid damage by removing the lids of our food boxes and zip tying them over the radiator grill. Furthermore the tyres need constant topping up, we are running at about 5 PSI so they are soft enough to roll over the stakes but the downside is they constantly leak air at the beads.

Our last camp in Shelburne was on a rise above one of those sandstone creeks. With a water wash to rid ourselves of the days grime, we sit around the campfire watching the mist rise from our damp boots and listen to the silence of this magical place.

In putting the history of this area together I would like to thank:

Lyndon Schneiders, The Cape York and Northern Australian Campaigner for The Wilderness Society.

and

Kerry Trapnell of the Cairns Regional Gallery for use of his photographs marked (*)

http://www.cairnsregionalgallery.com.au/focus-trapnell.pdf

Further research information from:

Cape York Peninsula Conservation and Land Management Environment Australia by Stanton J.P. (1997)

The Natural Heritage Significance of Cape York Peninsula by Mackey B., Nix H. and Hitchcock P. (2001)

Areas of Conservation Significance on Cape York Peninsula by Abrahams H. et al (1995)

Post Note in 2017

The area is still unfortunately still offers no access for non-indigenous Australians...

RETURN TO INTERNATIONAL TRAVELS